This is the first in a column focusing on classic albums associated with Ohio. Next time you see me I’ll be reviewing an album by probably the most famous group to have Ohio in their name. So famous I stole that name for the name of my column. Funny how that works.

The story of 1965’s Newport Folk Festival is rock legend—canonized as much as any album made by Bob Dylan, the Beatles, or Beach Boys. Dylan burst into some of the most raucous electric rock ‘n’ roll blues the audience had ever heard, alienating the fans and scandalizing the folk intelligentsia. He became a martyr of the folk press, hated by the people who once lifted him up. Boos filled the crowd (allegedly due to the sound quality of the speakers, not the sounds themselves).

But in the end, nobody in the Newport could stop Dylan’s ascension. Within the next two years the folk scene would move almost entirely away from traditionals, away from acoustics, and away from politics. The lineage of Dylan as the folk world’s shining star went to Joni Mitchell, who before long signaled the entire scene morphing into the Folk Rock California sound. While artists like Cosby, Stills, Nash, and Young could make songs like “Ohio”, they were equally at home making “Our House”. The move to California seemed like the death of a certain strand of politically focused songwriting. There was one exception, a songwriter whose political grit couldn’t be stopped, not in New York, California, or his home state of Ohio.

Phil Ochs was a perennial mover. The “singing journalist” had been born in Texas and spent his childhood years bouncing around New York state before settling into Columbus, Ohio as a teen and eventually attending THE Ohio State University. A writer for the still standing comedy magazine Sundial, he would win his first guitar near the end of his time at OSU after making a bet that John F. Kennedy would become president.

A few months before Phil Ochs moved out to California, he released his final folk album. A live album in which only new songs are featured and happened to be almost entirely recorded in a studio, Phil Ochs In Concert undersold expectations. Greatly. If Phil Ochs could sell out Carnegie Hall, why couldn’t he sell a record? His label theorized it was due to the liner notes which consisted of poems by Mao Ze-Dong with the text “Is This The Enemy?” (Ochs also slips this gem of a line into the album’s opener “And you’re supporting Chiang Kai-Shek while I’m supporting Mao”). While I couldn’t find the exact poems used, marxists.org has a collection of Mao’s poetry for the curious.

Despite the lack of sales, Ochs’ In Concert was another critical and artistic success. On In Concert Ochs would write not just about the major issues of the day (college protests, the Vietnam war) but also little remembered political episodes that even the leftists back then didn’t think twice about (nobody but Ochs would dedicate a song to Santo Domingo). While these songs are similar in topics to his earlier albums, Ochs also made a daring change during In Concert: the inclusion of autobiographical, nonpolitical tunes.

“There But For Fortune” would soon become Ochs most well known tune due to a cover by “Queen of Folk” Joan Baez. The track, which touches on American Foreign policy in the final verse, is mainly a meditation of fate, luck, and death. “Fortune” was Baez’s pop crossover, and the first honest to god hit either artist (both of whom were known mainly for political activism) would have. Up until the 70’s, when Baez went from primarily an interpreter to an acclaimed songwriter in her own right. Ochs, in a typical bit of self-deprecating humor, would often introduce the song as written for him by Baez. It was clear that he as an artist hungered for the opportunities that Baez and other folk artists were increasingly finding in California.

Ochs was one of the last of the New York scene to move out to California, yet he never thought too much about it. A transplant himself, he just couldn’t deny the career opportunities of California any further. If Dylan could turn pop, Ochs could follow. He moved out, signed with a new label, and began work on his fourth album, Pleasures of the Harbor.

Pleasures came in a dark time for America’s political music. While the Vietnam draft had already valorized many Americans towards political protest, the lottery system wouldn’t come into effect for a few more years. Anti-war activism was part of the counterculture, but it was an undercurrent to the hippie scene. The summer of love wanted Vietnam to end as much as it wanted to do acid and trip out.

What Ochs would become obsessed with was the avant-garde. Los Angeles had a thriving experimental rock scene in the late sixties. While Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention were undoubtedly the scene’s most well-known export, they were off in New York by the time Ochs came to California. Joe Byrd, who led a little known band named The United States of America, enamoured Ochs instead. The United States of America combined Ochs own leftist politics with early electronic noise. Having loved their self-titled record, Ochs invited Byrd to help arrange a song for his new album. The song was an eight minute long epic about the Kennedy assassination called “Crucifixion”. The only problem with the song is that Ochs wanted it to be a pop breakthrough. One who listens to this album is thus forced to draw two conclusions. One: Phil Ochs is superbly talented. Two: Phil Ochs has no commercial sense about him.

Pleasures of the Harbor gets better as it goes along, that is to say the first track/lead single shows everything that could potentially sink an album like this. It’s a sonically overstuffed, nearly maudlin, voice-stretcher. Ochs arrangements are big, bombastic, and beyond this world— threatening to distract from the song itself. I’ve seen the lyrics be called one of Ochs’ few love songs, although I don’t think it’s necessarily accurate. The song is about a verve for life despite the destruction of the world. In a word, it’s vague.

The album’s second track is actually worse. Pleasures would get flack for having its tracks run too long and go too slow, and nowhere is that more true than on “Flower Lady”; a six minute violin ballad with a barely recognizable melody and weak lyrical conceit. To my surprise, “Flower Lady” would become a semi popular track to cover, with acts like Jan and Dean doing renditions of it. Someone listening to Pleasures of the Harbor would be right to panic about Ochs new musical direction.

Three tracks in Pleasures of the Harbor finally reveals itself to the patient listener, both lyrically and musically. “Outside a Small Circle of Friends” brings to life the album’s dominant musical force, ragtime jazz. Ochs voice, in a move nobody would expect, fits in perfectly. He also reveals himself to have an ear for pop-jazz arrangements. Together with band pianist Lincoln Mayorga (who does great, hyperactive work here) and arranger Ian Freebairn-Smith they convincingly transport ragtime to modern times. I also scoured the internet for details on the drummer for this song, whom I cannot find for the life of me.

The lyrics are also a return to form for Ochs. He’s back to singing about politics; taking the murder of Kitty Genovese, a bartender stabbed outside her apartment in Queens, as an example of people’s larger apathy. After Genovese’s murder, the New York Times published a story stating that thirty seven of her neighbors saw or heard the attack, and that nobody helped. The Times’ story would later be disproven, but the psychological studies in its wake did show a real effect of apathy. Ochs uses it to slam people who don’t care about violence, inequality, or democracy. He was also insistent on having this ragtime number become a single.

Ochs final album, (1970s Greatest Hits, which consisted solely of new songs) had Ochs dawning a yellow gold Lamé suit (a la Elvis) on its cover. Ochs rationale? “If there’s any hope for a revolution in America, it lies in getting Elvis Presley to become Che Guevara.”

If there’s one quote that sums up the California half of his career, that’s it. Pleasures of the Harbor came before Ochs would be truly radicalized during the 1968 democratic national convention, but the hunger to get his politics (and name) to a wider audience was clear as day. He knew intuitively that “Outside A Small Circle of Friends” was his best shot, so why make it a ragtime? The most likely answer is, like most else in 60s music, the Beatles.

The Beatles were riding high off of the success of their landmark album Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band (a.k.a The Most Important And Canonized Rock ‘N’ Roll Album of All Time) and the incredibly successful singles that followed it (collected in the states as Magical Mystery Tour, which in the UK was a double EP of soundtrack cuts from a doomed TV Movie). In the middle of both these albums was a piano based music hall track (“When I’m Sixty Four” and “Your Mother Should Know”). It could be reasonably seen as the British’s non-bluesy, never-hip ragtime. With Ochs Beatles fandom in mind, it’s not a stretch to imagine Ochs, who always had a knack for writing from other people’s perspective, being influenced by those songs and McCartney’s usage of older music to incite older characters.

“Outside A Circle of Friends” would be released as the album’s second single. Met with critical success and radio success, the 7″ had apparently validated all of Ochs commercial ambitions. The promo single, backed with album cut “Miranda”, another ragtime number, gained near immediate traction in San Francisco. Yet, just before the single went to national success and got to the top 100, as Billboard would predict, A & M records began getting complaints. People were fine with the references to rape, murder, and segregation, yet the one line “smoking marijuana is more fun than drinking beer” proved too scandalous for the public writ large. Two alternate versions were produced without the line, but it was too late. Ochs best shot at national fame just passed him by; his career would never be the same.

Before side one ends, there’s one more song: “I’ve Had Her”. A beautifully arranged piece of poetic misogyny. Ochs had often played characters in songs before, but normally for the purpose of political satire. On this cut, Ochs muddies the water between character and singer, could our progressive folksinger really think to write “I’ve had her, she’s nothing”. Is she even a real woman? While someone like Dylan would often use their songs to put down women imaginary and real, Ochs normally saved his anger for capitalism, imperialism, and other political forces. Even then, is “I’ve Had Her” even anger? He uses his highest register of an already schoolboy tenor, it sounds like saddened pity more than anything. Then that begs the question: pity for the man or the woman? It’s a piece marked by questioning, offering no easy answers.

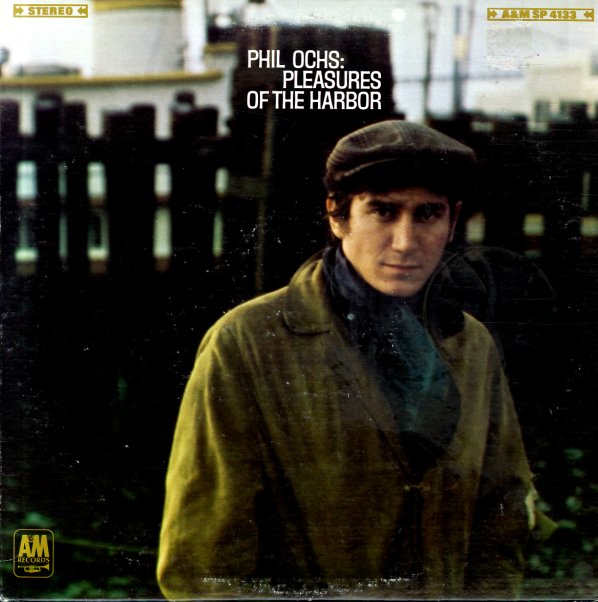

It is at this moment that another fact about Pleasures becomes unavoidable. The album is a downer. More than its optimistic title, it evokes its cold and desolate cover. It evokes an image of the artist as a man who can no longer be called young. Whereas the cover of Ochs breakthrough album I Ain’t Marching Anymore looked determined. He seems lost on the cover of Pleasures of the Harbor; a metaphor for an album on shifting tides, sounds, and ideologies. He is stuffed in layers and layers of cold, trying to avoid a New York cold that doesn’t exist in California.

“Miranda” and “The Party” are a pair of character pieces. “Miranda” closes side one with the album’s jazziest number, detailing the days of the titular libertine dancer and “Rudolph Valentine fan”. Once more, apathy is an undercurrent, Miranda doesn’t “claim to understand” the world around her, she simply chooses to enjoy life no matter how bad it gets. The song is slightly surreal (“And everyone’s inviting you/To look upon their operation scars”) in its attention to character and detail, the type of tune to make one wonder what a second character as a novelist would’ve looked like for Ochs. Also found is a reference to Ochs FBI file, which was released after his death and contained about 500 pages on Ochs as a danger to the United States of America (“In the bar we’re gin and scotching/While the FBI is watching”).

The characters found in “The Party” are equally as privileged as “Miranda”. Ochs sings about bougie characters who find it tough enough to choose between vague centrist views and complete apathy. To entertain themselves they’ll indulge in cruelty and faux revolution. Just before you could accuse Ochs of being too judgemental, his narrator realizes he’s just another rich man. The narrator belies an apathy to the rich, to his surreal world, eventually to himself. The song is an artist (in this song Ochs plays a pianist for a fancy cocktail party) alienated from his art.

In “Miranda” and “The Party” we get the clearest theme of the album: you can enjoy life now, but it’s only so long before the world finds you.

Just before In Concert deep cut, “Ringing of Revolution”, Ochs remarks that the song is among his most cinematic. He had been a movie lover since childhood, frequenting movie houses and devouring country and western films. Before folk music and leftism were a part of his life, Phillip was raised on John Wayne and patriotism. “Pleasures of the Harbor” would then be his second ultra cinematic film-song. Its languid pace evokes an old Hollywood epic and the lyrics evoke an unreal bohemia in ultra detail. The lyrics are about two of his most archetypical characters: a sailor and the prostitute he visits during his day back from war. After the thrill of his encounter is over, he is pulled back to his old life. In the end, he finds himself again yearning for the distraction that did him no good earlier. Like many stories on the album, “Pleasures of the Harbor” finds hedonism coming up short. Yet, unlike the cold mockery of “Small Circle” or the twisted surrealism of “Miranda”, Ochs seems to be empathetic to his characters and their troubles. The chorus is one of the most soothing he ever wrote, with the friendliest melody he ever put his words to. “Soon your sailing will be over/come and take the pleasures of the harbor”. It’s not hard to imagine the ocean as the hardships of life, and the harbor as a sort of heaven. There’s an almost childlike innocence to the song, heightened by the angelic harp and glockenspiel. An innocence that would get shattered very soon.

In Ochs career, which is as filled with New York Hipster history and lore as anyone else’s, one of the more famous tales is playing Crucifix for Robert F Kennedy. The then presidential hopeful broke down in tears realizing it was about his brother. The song, Ochs longest, was an all encompassing thread of American kill-your-heroes paranoia. The song, which compares John F Kennedy to Jesus is smothered in avant-garde electronics. Even in the song’s gargantuan length, there was no room to breathe.

219 days after the release of Pleasures, Robert Kennedy was shot and killed. Later that summer, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago would end in riots and police brutality. Ochs would witness it all. His first album after the convention, Rehearsals for Retirement would show Ochs grave on the cover, with text reading that he died in Chicago. In many ways, Pleasures Of the Harbor shows an alternate vision of America that was killed in Chicago. The songs are dark and opaque, but beneath the cynicism there are genuine love songs, there is genuine hope, and there may be a way out of political hell. Whether that door is open in 2025, or if American greed and apathy has slammed it shut, is up to the listener.

Leave a Reply